The Art of Modernizing Historical Recipes

Plus a delectable Ancient Roman recipe for a sauce for duck!

This is one of my more popular posts from a couple of years ago, and I thought it deserved a revisit. I hope you don’t mind the repost—I’m taking a short break but will be back in mid-April with plenty of book updates and Italy stories to share. See you soon!

Transforming Recipes from Old to New

I have no idea what a flamingo tongue tastes like. The Elder Pliny tells us in his Encyclopedia of Natural History that the ancient gourmand, Apicius, said that they have “a specially fine flavor.” I also have no idea if milk-fed snails are delicious or if boiled sow’s womb would satisfy the palate. Wealthy ancient Romans loved these dishes, however, and the recipes for cooking them survive in the earliest known cookbook, Apicius’s De Re Coquinaria.

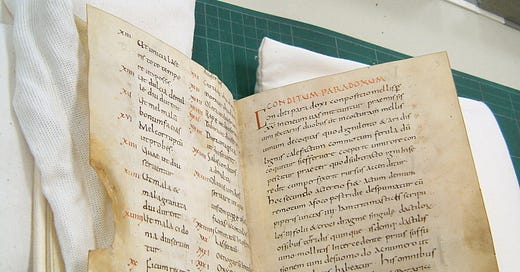

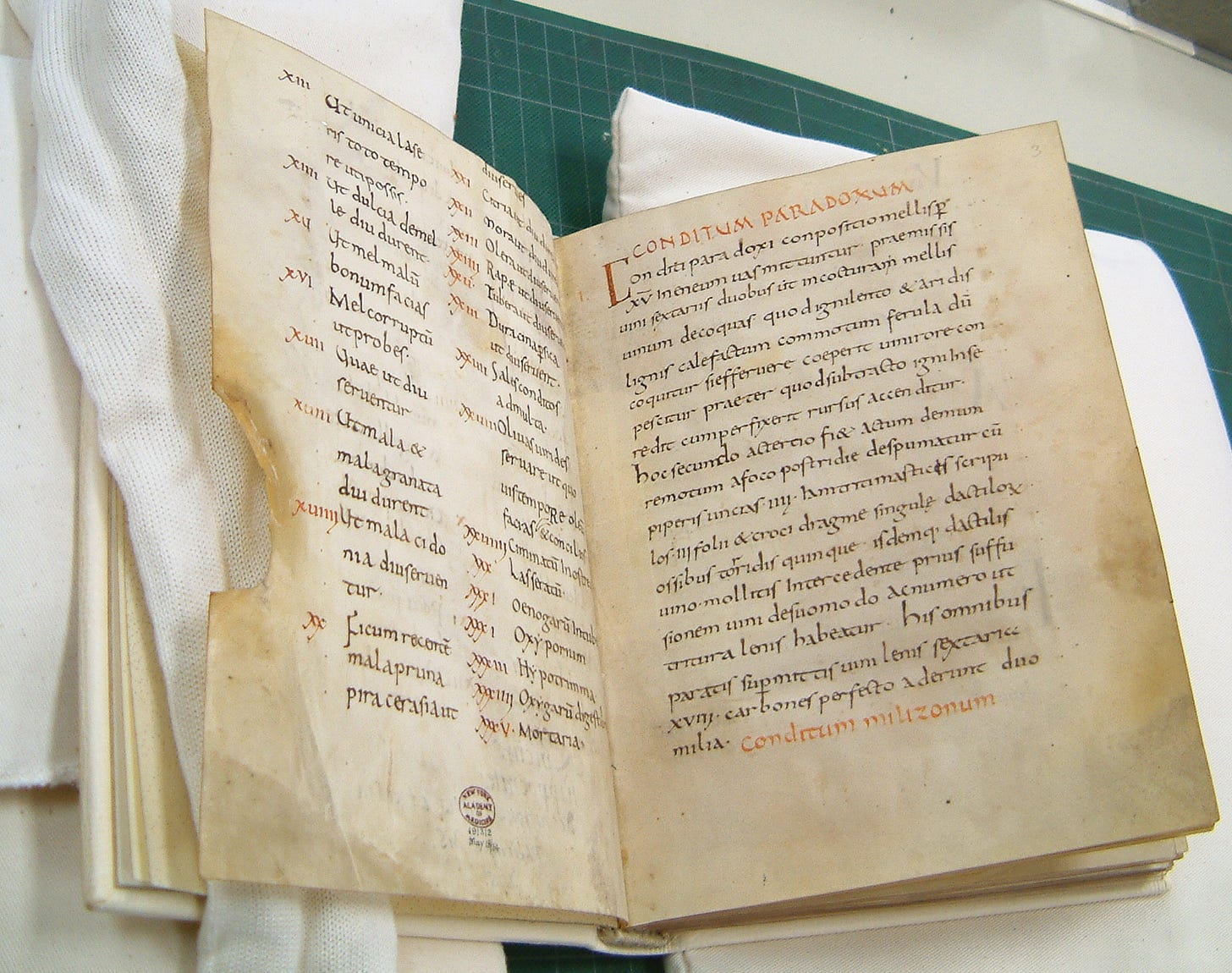

The Apicius cookbook that we know today is a cobbled-together batch of recipes from the third or fourth centuries C.E., but many of the recipes within hail from centuries earlier. It is suspected that several recipes named for Apicius may have originally come from the kitchens of the famous food lover himself.

If you’ve read my novel, Feast of Sorrow, you already know that Marcus Gavius Apicius was an extraordinarily wealthy Roman that lived during the time of Emperor Tiberius. In reality, we know only a few tidbits about his life, one of which is his very dramatic death. Since what we primarily know of Apicius and his life revolves almost entirely around food, and the most important legacy that is left related to him is the De Re Coquinaria cookbook, I had a challenge on my hands. Namely, how was I to write about food that had never tasted and that had ingredients that I largely had never heard of before?

Fortunately, I wasn’t the first to explore the food of Apicius. Food historian Sally Grainger, the translator of the Apicius cookbook, published a companion cookbook, and other food historians, such as Mark Grant, Andrew Dalby, Francine Segan, and Ilaria Gozzini Giacosa had already published cookbooks that helped modernize the recipes for today’s audiences. I began there, cooking everything from Parthian chicken to bread to honey cakes.

Many of the recipes are already familiar to us – French toast, frittatas, fried dough, mustard beets, and more. It was the ingredients for the other dishes that proved to be the biggest challenge for me. In 2008 when I began writing the book and testing the recipes, it was very difficult to find some of the spices or the cuts of meat. Now you can find virtually anything you want via the Internet, be it asafoetida (the closest taste to the ancient herb silphium), fish sauce (Italian colatura), or date sauce.

Historians know a lot about how Roman chefs might have cooked, having unearthed many of the clay and brass pots and utensils from various archaeological sites, particularly Pompeii. Foods would have been cooked over a fire, and since I live in an apartment, such a re-creation wasn’t something possible or desirable for me.

In the beginning, I primarily cooked from the translations found in the cookbooks by the authors mentioned above. Gradually, as I began to understand the ingredients better, I became more adventurous, interpreting the recipe directly. What is interesting about De Re Coquinaria is that it’s a book for other chefs, chefs who probably knew the methods of cooking during the time that the book was first scribed. Each recipe is a list of ingredients without measurements and only a rudimentary set of instructions.

That meant I could interpret the dish in whatever way I wanted. It led to great experimentation in the kitchen to get a dish right. Fish sauce and asafoetida are very powerful, so toying with those ingredients to get the right balance was key. Sometimes, it made sense to add something. For example, the recipes don’t call for olive oil, but our methods of cooking in the pan might require it. What mattered most to me was the flavors. Could I be as true as possible to the ingredients and yet make them palatable for the modern audience?

Those of you who know me well know I also had another challenge on my hands—I’m not partial to fish. And garum is literally in every ancient Roman dish, and I wasn’t sure how I was going to do it. But what my husband and I found is that very little goes a long way. This makes sense, for it’s what the Romans used in lieu of salt to flavor the food (salt was primarily a preservative), and it gives dishes a wonderful umami flavor.

If you want to know all about garum, Sally Grainger is the number one expert on it. Here she describes everything you might want to know about this condiment, which was as ubiquitous as ketchup to the ancients, so much so that there were factories across the Empire devoted to making it.

You can also pick up her book, The Story of Garum to learn more.

Cooking the recipes of Apicius meant that my descriptions of meals in the book are more accurate. It also gave me a sense of what the smells of the kitchen and the textures of the ingredients might be.

One of the greatest joys of writing books about food has been testing and trying out the various recipes. Every era has its own sort of flavor. Ancient Rome is very distinct, with savory, umami undertones to everything. The Renaissance is over-the-top sweet and spice. The Baroque era is also over-the-top, certainly in presentation, but in the food, you can start to see a better balance of savory and sweet and more moderation on the heavy sugar and spices.

The Apicius cookbook contains over a hundred recipes for sauces. Here is one that I interpreted that has become one of our favorites to make.

Sauce for Duck

(recipe translated from Latin by Christopher Grocock and Sally Grainger in Apicius p.223, recipe interpretation by me)

Apicius 6.2.1 Sauces for crane or duck, partridge, turtle-dove, wood-pigeon, dove, and various other birds.

Wash and dress (the bird) and put in a large cooking pot; add water, salt, and dill; cook it until it is firm, halfway through the cooking process; take it out and put it in another pan with oil and liquamen and with a bundle of oregano and coriander. When it is almost cooked, add a little defrutum to add color. Pound pepper, lovage, cumin, coriander, laser root, rue, caroenum, and honey; pour on some of the cooking liquor, and flavor with vinegar. Pour this back into the pan so that it warms through. Thicken with starch. Put the bird on a serving dish and pour the sauce over.

This is a wonderfully flavorful sauce that we pair with duck. We tend to sous vide the duck, but it’s much faster and equally good to sear it in the pan.

Some notes:

Of course, we have to make some substitutes for ancient Roman ingredients. I link to places to purchase in the recipe, but to explain:

Liquamen is another term for garum, a sauce made from anchovies. Colatura is the modern Italian equivalent, but you can also use Thai Nam Pla or Vietnamese Nuoc Nam Mhi, which are quite similar to the ancient Roman garum.

Caroenum and Defrutum are both grape syrups, made by cooking the liquid down by different amounts. In this dish as substitutes, I’m using sweet wine, and the wonderful Italian condiment, vincotto.

Lovage is not common in the US but is becoming more available via specialty shops or Amazon, which I’ve linked to in the recipe below. It’s worth trying to get it, as it really makes a difference in the dish. I’ve opted to leave out rue, because it’s difficult to acquire, and it’s extraordinarily bitter. Plus, there is already a lot going on in the dish.

Serves 4

2 lb duck breast

Salt and pepper to taste

1 tsp ground coriander

1 tsp lovage (celery leaves or flat-leaf parsley can substitute but definitely not the same)

1 tsp cumin

1/4 tsp asafoetida (or 2 cloves garlic…again, not the same, but it works)

2 tbsp honey

2 cups of sweet wine (I use the Greek Kourtaki Samos Muscat wine but raisin wine or other sweet wines will work)

2 tsp sherry vinegar

2 tbsp vincotto

1 tsp fish sauce

A few sprigs of fresh dill

A few sprigs of fresh oregano

Combine all ingredients through the colatura. Whisk together and set in a small saucepan over low-medium heat until reduced to 1/4 and slightly thick. You can remove the sauce from the heat until the duck is ready and then warm it before serving.

Score the skin side of the duck and salt and pepper both sides.

Add the duck to a pre-heated medium heat pan, skin side down.

Sear the skin side for about four minutes or until skin is crispy. Sear the other side for about two minutes. Flip it back over and sear the skin side for another minute. This will cook the duck to medium-rare, which is the most common way to eat it. For more info on cooking duck and duck temperature, head here.

Remove the duck from the pan and let it rest for ten minutes. Make sure to let it rest or it will be bloody on the plate.

Bundle together the tops of the sprigs of dill and oregano with string to create a bouquet garni. If using celery leaves or parsley in place of lovage, you can add to the bouquet instead of the sauce. Add the bouquet garni to the melted duck fat, swirling it around to flavor the oil and meat.

Remove the bouquet from the duck fat and add a teaspoon of the fat to the sauce to impart a little more flavor to the completed sauce.

Pour over the duck and serve.

Mangia!

What’s Bringing Me Joy This Week

This is my favorite Cure song.

New Saint Motel vid out! Can’t wait to see them in Boston this spring.

I’ve been playing this fun game, Eternal Strands, as a source of distraction.

Thanks for Joining Me

If you love food and love Italy, and haven’t read THE CHEF’S SECRET or FEAST OF SORROW, click the links to learn where to buy your copy! And now you can order my latest, IN THE GARDEN OF MONSTERS!

You can also follow me here: Website | Instagram | Facebook | Threads | Bluesky